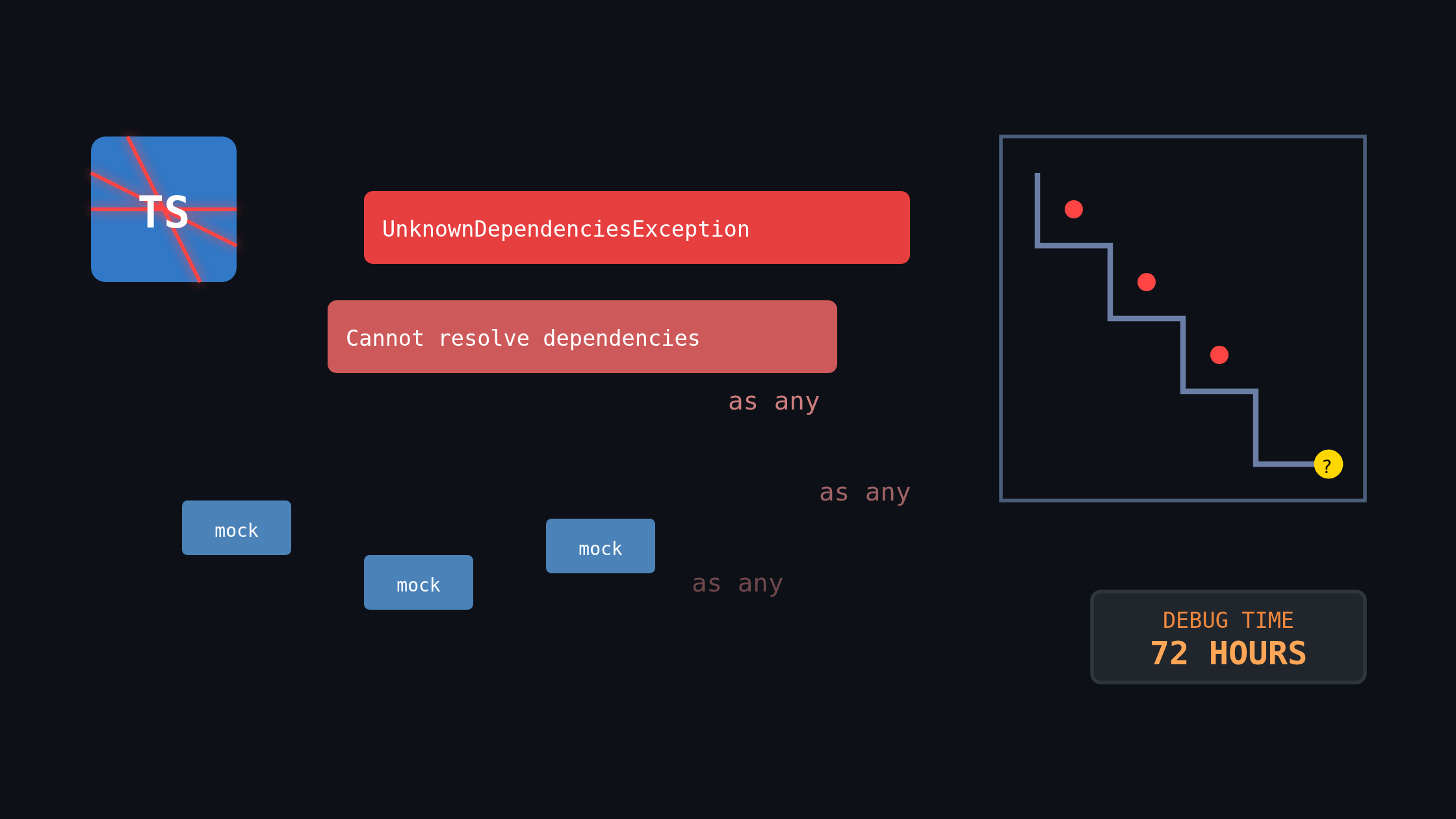

How a 72-hour debugging nightmare revealed the fundamental flaw in dependency injection frameworks and why strict typing matters more than sophisticated abstractions

The Promise vs. The Reality

TypeScript sold us a dream: JavaScript’s flexibility with compile-time safety. NestJS took that dream further: enterprise patterns with type checking. For backend development, this seemed like the perfect combination, until a simple refactoring turned into a multi-day debugging marathon that exposed the fundamental contradiction at the heart of modern Node.js development.

The story begins with what should have been a straightforward task: refactor our notification system to route messages through a gateway instead of calling external APIs directly. Classic enterprise architecture, improve separation of concerns, centralize integrations, make everything more testable.

What followed was 72 hours of dependency injection archaeology, token naming inconsistencies, mock configuration hell, and ultimately discovering that a perfectly typed, fully tested, 93% code coverage system was completely broken in production.

This isn’t just another “framework bashing” story. This is about a fundamental architectural mismatch between the tools we choose and the problems we’re actually trying to solve. It’s about how TypeScript’s safety guarantees systematically break down in dependency injection frameworks, and why the choice between flexibility and correctness matters more than we admit.

Day 1: The Dependency Injection Type Safety Illusion

The refactoring started innocently enough. Our original notification service was beautifully simple:

@Injectable()

class NotificationService {

constructor(

@Inject('EXTERNAL_API') private externalApi: ApiClient,

private templateEngine: HandlebarsService

) {}

async sendMessage(template: string, data: any) {

const processed = this.templateEngine.process(template, data);

await this.externalApi.sendMessage({

text: processed,

blocks: this.buildRichBlocks(data)

});

}

}Direct, clear, functional. But according to our enterprise architecture guidelines, it was tightly coupled. The refactored version would route everything through a gateway service:

@Injectable()

class NotificationService {

constructor(

@Inject('GATEWAY_SERVICE') private gateway: ClientProxy

) {}

async sendMessage(messageData: MessagePayload) {

await this.gateway.emit('send_notification', messageData);

}

}Cleaner separation of concerns, centralized external integrations, more testable architecture. What could go wrong?

Everything.

When I ran npm test, every single one of our 45 test suites failed. The error message was a masterpiece of unhelpful verbosity:

UnknownDependenciesException [Error]: Nest can't resolve dependencies

of the NotificationService (?, ConfigService, AmqpConnection,

EventSqService, SqService, UserRepository).

Please make sure that the argument "GATEWAY_SERVICE" at index [0] is

available in the NotificationModule context.

Potential solutions:

- Is NotificationModule a valid NestJS module?

- If "GATEWAY_SERVICE" is a provider, is it part of the current NotificationModule?

- If "GATEWAY_SERVICE" is exported from a separate @Module, is that module imported within NotificationModule?Here’s the fundamental problem: TypeScript cannot verify that the 'GATEWAY_SERVICE' token actually exists, that it points to something implementing ClientProxy, or that your test mocks match the real implementation. You get all the ceremony of dependency injection with none of the safety guarantees.

In plain Node.js, this would be const gateway = require('./gateway'). If the module doesn’t exist, you get an immediate error. In NestJS, you need to understand module imports and exports, provider registration, token-based injection, service factory functions, and circular dependency detection. The next three hours were spent in what I call “dependency injection archaeology”—digging through layers of module definitions to understand why NestJS couldn’t find a service that clearly existed.

The Token Naming Catastrophe

The investigation revealed the root cause: inconsistent token values across files. Some used one string, others used completely different values:

// In constants file

export const GATEWAY_SERVICE = 'GATEWAY_SERVICE';

// But some modules use

export const GATEWAY_SERVICE = 'RESOURCE_MANAGER_CLIENT';

// And tests use different values entirely

export const GATEWAY_SERVICE = 'MOCK_GATEWAY_SERVICE';

// With inconsistent usage across files

@Inject('GATEWAY_SERVICE') // Module A

@Inject('RESOURCE_MANAGER_CLIENT') // Module B

@Inject('MOCK_GATEWAY_SERVICE') // TestsThe real problem was that string-based dependency injection allows these mismatches to compile successfully but fail at runtime. In a language with type-based dependency injection, you’d depend on actual interfaces rather than string tokens, eliminating this entire category of lookup errors. It took three hours to standardize token usage across fifteen files just to get dependency injection working again.

The Template Processing Archaeology

Removing the Handlebars dependency seemed straightforward, just replace Handlebars.compile() with a simple regex:

// Replace this

const template = Handlebars.compile(message);

const result = template(data);

// With this

const result = message.replace(/{{(w+)}}/g, (match, key) => data[key]);But our codebase had organically evolved multiple incompatible template formats. Some used {{player_name}}, others used <<player name>>. Some had underscores, others spaces. What started as a simple regex replacement became a complex parsing problem:

protected processTemplates(text: string, data: any): string {

if (!text) return text;

let processed = text;

// Handle URL templates

for (const [key, value] of Object.entries(this.urlMappings)) {

const placeholder = key.replace(/_/g, ' ');

const regex = new RegExp(`<<${placeholder}>>`, 'gi');

processed = processed.replace(regex, value);

}

// Handle user mentions - but leave these for the gateway

// Don't process <<player name>> here

return processed;

}This problem reveals how framework complexity can obscure organizational issues. The template format inconsistency was fundamentally a process problem—lack of code review discipline and no centralized template processing strategy. But the framework’s layered abstractions made this duplication harder to spot during development.

With template processing scattered across multiple services behind dependency injection boundaries, each individual change looked reasonable in isolation. A developer adding <<variable>> syntax in one service wouldn’t necessarily see that another service was already using {{variable}} syntax, especially when the processing logic was hidden behind service interfaces.

If we had used direct string manipulation without framework abstractions, the regex patterns would have been more visible in the codebase. Duplication would have been more obvious during code reviews. The processing logic would have been concentrated in fewer, more discoverable places.

The framework didn’t create the inconsistency, but its complexity provided more places for the inconsistency to hide and grow unnoticed. Four hours of debugging time that could have been prevented with better code review practices, but was made more expensive by architectural complexity.

The Constructor Signature Cascade

Changing the NotificationService constructor signature broke every test that instantiated it. The mocks weren’t just interface changes, they represented fundamentally different interaction patterns:

// Before - every test file

const mockExternalApi = {

sendMessage: jest.fn(),

getUserInfo: jest.fn(),

// ... 20 more methods

};

const mockTemplateEngine = {

compile: jest.fn(),

process: jest.fn(),

// ... more methods

};

// After - every test file

const mockGateway = {

emit: jest.fn(),

send: jest.fn(),

// Completely different interface

};Each of the twelve test files took 45 minutes to update. We went from mocking API clients to mocking message brokers, which required completely different setup patterns. By the end of day one, all tests were passing again, but I did spent nine hours on what should have been a simple refactoring.

Day 2: The Mock Testing Catastrophe

The testing story reveals the deeper issue with TypeScript safety in NestJS. Comprehensive mocking requires abandoning type safety precisely where you need it most:

const mockGateway = {

emit: jest.fn(),

send: jest.fn(),

// Missing methods? You'll find out at runtime

// Wrong signatures? any defeats checking

} as any; // White flag of surrender to type safetyThat as any isn’t a bug—it’s the only way to make NestJS mocking work efficiently. You’re telling TypeScript “I don’t care about types” in your tests, which defeats the entire purpose of using TypeScript in the first place.

The elaborate test setup required for NestJS shows how far we’ve strayed from simple, verifiable code:

describe('NotificationService', () => {

beforeEach(async () => {

const module = await Test.createTestingModule({

providers: [

NotificationService,

{

provide: 'GATEWAY_SERVICE',

useValue: mockGateway,

},

{

provide: ConfigService,

useValue: mockConfigService,

},

{

provide: AmqpConnection,

useValue: mockAmqpConnection,

},

{

provide: EventSequenceService,

useValue: mockEventSequenceService,

},

{

provide: SequenceHandlerService,

useValue: mockSequenceHandlerService,

},

{

provide: getRepositoryToken(PlayerSession),

useValue: mockRepository,

},

// ... 10 more mock services

],

}).compile();

});

});More time spent setting up mocks than writing actual tests. Mocks drift from real implementations. Complex dependency chains require understanding the entire service graph. Test failures often mean mock setup issues, not actual bugs.

After fixing all the dependency injection issues and achieving perfect test coverage, I deployed to dev. The tests were green, coverage was high, and the code looked clean. Then we tested the actual feature.

Expected: Rich interactive message with welcome text and action buttons Actual: Plain text saying “Start session 27”

Day 2: When 93% Coverage Meets 0% Functionality

This is the nightmare scenario of modern testing: comprehensive mocks validating that your abstractions work as designed, while your actual feature is completely broken. We had tests verifying that gateway.emit was called with the right parameters, but no tests checking whether messages actually rendered correctly:

// Test passes

it('should send message', async () => {

await service.sendMessage(mockMessage);

expect(gateway.emit).toHaveBeenCalledWith('send_notification', mockMessage);

});

// Real world fails

// External API shows text instead of rich blocksThe investigation began. Where was the problem? The notification service building messages? The gateway service forwarding them? The external API integration? The external service itself?

I started tracing through the logs. The notification service was processing notifications correctly:

{

"level": "debug",

"msg": "Processing notification",

"payload": {

"template": "Welcome to {{scenario_name}}...",

"data": {"scenario_name": "First Day", "player": "John"}

}

}The gateway service was receiving send_notification events with perfect payload structures:

{

"level": "debug",

"msg": "Received send_notification event",

"payload": {

"channel": "test-channel-123",

"text": "Start session 27",

"blocks": [

{

"type": "section",

"text": {

"type": "mrkdwn",

"text": "Welcome to First Day, it is time to meet the team..."

}

},

{

"type": "actions",

"elements": [

{

"type": "button",

"text": {"type": "plain_text", "text": "Start"},

"action_id": "START_LEVEL"

}

]

}

]

}

}The external API was receiving the data correctly and responding successfully:

{

"level": "debug",

"msg": "Sending message",

"request": {

"channel": "test-channel-123",

"text": "Start session 27",

"blocks": [/* same blocks as above */]

},

"response": {

"ok": true,

"channel": "C1234567890",

"ts": "1234567890.123456"

}

}Every layer was working correctly in isolation, but the end result was wrong. This was maddening. I spent the next six hours investigating whether our template processing was corrupting the JSON, checking character encoding, validating block syntax, and testing message size limits. Everything looked correct.

The Framework Wild Goose Chase

The framework’s abstractions led me down multiple dead ends. Initial theories included:

- “The session service isn’t building blocks correctly”

- “The gateway service isn’t forwarding blocks properly”

- “There’s a serialization issue between services”

- “The template processing is corrupting the JSON structure”

I spent hours debugging the wrong layers entirely, tracing through framework internals instead of questioning external assumptions. The sophistication of the abstractions made it feel like the problem must be in our code, not in something as simple as API field precedence.

Day 3: The One-Line Revelation

Starting day three, I decided to stop assuming the problem was in our code and start questioning external assumptions. Maybe the external API was working correctly, and the problem was in how it prioritizes different message fields.

I dove deep into the external API documentation and found this buried section:

The text, blocks and attachments fields

The usage of the text field changes depending on whether you’re using blocks. If you’re using blocks, this is used as a fallback string to display in notifications. If you aren’t, this is the main body text of the message.

When both text and blocks are present, the text field takes precedence as the main message content.

There it was. The smoking gun. The reason 24 hours of debugging had yielded nothing.

When both text and blocks fields are present, the external API uses text as the primary content and treats blocks as secondary. We were sending both fields, so the API was showing our fallback text instead of our rich blocks.

The fix was embarrassingly simple:

// Before (broken)

const message = {

channel: data.channel,

text: processedText, // API prioritizes this

blocks: richBlocks // Over this

};

// After (working)

const messageText = data.blocks ? '' : processedText;

const message = {

channel: data.channel,

text: messageText, // Empty when blocks present

blocks: richBlocks

};One line of logic. After 24+ hours of debugging across multiple services, extensive logging, JSON corruption theories, template processing investigations, and dependency injection archaeology.

The Testing Aftermath

Of course, the one-line fix broke several existing tests that expected different behavior:

// This test was now wrong

expect(apiClient.sendMessage).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

text: 'Expected text', // Now expects empty string

blocks: expectedBlocks

});

// Had to become this

expect(apiClient.sendMessage).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

text: '', // Empty when blocks present

blocks: expectedBlocks

});Required updating four test files and adding three new test cases to cover the text/blocks interaction logic. Two more hours updating tests for a one-line code change.

The Fundamental Type Safety Problem

This experience crystallized a fundamental insight about TypeScript and dependency injection frameworks. Compare the debugging experience to what the same refactoring might look like in Go:

type NotificationService struct {

gateway GatewayClient // Interface verified at compile time

}

func NewNotificationService(gateway GatewayClient) *NotificationService {

return &NotificationService{gateway: gateway}

}

func (s *NotificationService) SendMessage(msg MessagePayload) error {

return s.gateway.Send("send_notification", msg)

}If gateway doesn’t implement GatewayClient, the code won’t compile. No tokens, no runtime injection failures, no module archaeology. The dependencies are explicit in the constructor signature.

Testing becomes straightforward:

type MockGateway struct {

LastEvent string

LastPayload MessagePayload

}

func (m *MockGateway) Send(event string, payload MessagePayload) error {

m.LastEvent = event

m.LastPayload = payload

return nil

}

func TestSendMessage(t *testing.T) {

mockGateway := &MockGateway{}

service := NewNotificationService(mockGateway)

err := service.SendMessage(testMessage)

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, "send_notification", mockGateway.LastEvent)

assert.Equal(t, testMessage, mockGateway.LastPayload)

}If MockGateway doesn’t correctly implement GatewayClient, it won’t compile. The compiler enforces that mocks match interfaces without escape hatches. No as any, no token mismatches, no runtime surprises.

Where TypeScript’s Promise Breaks Down

TypeScript promises type safety, but NestJS patterns systematically undermine it:

@Inject()tokens bypass type checking entirelyanytypes in test mocks disable verification where it matters most- Reflection-based decorators hide runtime behavior from static analysis

- Module resolution happens at runtime, not compile time

- Complex dependency graphs obscure simple integration failures

You end up with TypeScript’s complexity overhead without its safety benefits. The type system becomes theater, present for developer confidence but absent when you actually need protection.

The Architecture Mismatch

The deeper issue was architectural: we chose enterprise patterns before we had enterprise problems. A 6-person team building a straightforward notification service doesn’t need sophisticated dependency injection, modular architecture, or decorator-driven development.

We optimized for coordination problems we didn’t have while creating debugging problems we did have. The “enterprise ready” patterns became obstacles to shipping working software.

The refactoring story reveals the hidden costs of sophisticated frameworks:

- Development Time: 3 days instead of planned 1 day

- Debugging Time: 24+ hours for a one-line fix

- Test Maintenance: Updates across 16 test files

- System Complexity: Simple direct calls became multi-service orchestration

- Knowledge Requirements: Team needs to understand dependency injection, module systems, message patterns, cross-service debugging

The Backend Development Reality Check

Backend services have specific requirements that expose these weaknesses:

Runtime Failures Are Expensive: A dependency injection failure can bring down production services. Compile-time verification prevents entire categories of deployment issues that no amount of testing can catch reliably.

Debugging at 3 AM: When services fail in production, you need stack traces pointing to actual code, not framework internals. Six developers tracing through dependency injection chains is waste.

Performance Under Load: Reflection overhead and dynamic resolution costs accumulate in high-throughput services. Direct function calls have predictable performance characteristics.

Team Coordination: The complexity should be in business logic, not in framework mechanics. Understanding your domain is hard enough without also needing to understand framework archaeology.

The Language Choice Implications

This experience revealed a fundamental tension in backend development: flexibility versus safety. JavaScript and TypeScript optimize for rapid prototyping and developer expressiveness. Strictly typed languages optimize for correctness and long-term maintenance.

For backend services where bugs have real business impact, correctness often matters more than expressiveness. The ability to ship fast doesn’t matter if what you ship doesn’t work reliably.

Go’s approach—explicit dependencies, compile-time verification, simple patterns—aligns better with backend development requirements. You sacrifice some expressiveness for much stronger guarantees about correctness.

Consider how the same service structure looks in Go:

type NotificationService struct {

httpClient *http.Client

config *Config

logger *slog.Logger

}

func (s *NotificationService) SendMessage(ctx context.Context, msg Message) error {

payload, err := json.Marshal(msg)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to marshal message: %w", err)

}

req, err := http.NewRequestWithContext(ctx, "POST", s.config.GatewayURL, bytes.NewReader(payload))

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create request: %w", err)

}

resp, err := s.httpClient.Do(req)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to send request: %w", err)

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

if resp.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

return fmt.Errorf("gateway returned error: %d", resp.StatusCode)

}

return nil

}No dependency injection framework. No complex module system. No token-based provider registration. No extensive mock configurations. Stack traces point to actual code. External API behavior is immediately obvious. Dependencies are explicit and compile-time verified.

Testing requires no framework magic:

func TestNotificationService_SendMessage(t *testing.T) {

server := httptest.NewServer(http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

assert.Equal(t, "POST", r.Method)

assert.Equal(t, "application/json", r.Header.Get("Content-Type"))

var msg Message

err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&msg)

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, "test message", msg.Text)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

}))

defer server.Close()

config := &Config{GatewayURL: server.URL}

service := &NotificationService{

httpClient: http.DefaultClient,

config: config,

logger: slog.Default(),

}

err := service.SendMessage(context.Background(), Message{Text: "test message"})

assert.NoError(t, err)

}No mocks needed—just spin up a test server and verify the actual HTTP behavior. The test validates that the service correctly constructs requests and handles responses, not that it calls mocked methods with expected parameters.

The Hidden Costs of Sophisticated Frameworks

NestJS provides genuine value for large teams building complex systems. The modular architecture, built-in patterns, and comprehensive ecosystem solve real coordination problems. But that value comes with costs that aren’t obvious until you pay them:

Cognitive Overhead: Understanding framework mechanics instead of business logic. Every team member needs to understand dependency injection, module systems, decorator patterns, and testing frameworks.

Debugging Complexity: Multiple abstraction layers obscuring simple problems. When something breaks, you debug through framework internals instead of your actual code.

Testing Theater: High coverage masking low effectiveness. Extensive mocking validates that your abstractions work as designed, not that your business logic produces correct outcomes.

Runtime Surprises: Type system failures in production. Token mismatches, circular dependencies, and configuration errors that compile successfully but fail at runtime.

For teams building straightforward services, these costs often exceed the benefits. The framework optimizes for problems you don’t have while creating problems you can’t solve efficiently.

When Enterprise Patterns Actually Pay Off

The refactoring was ultimately successful despite the pain. The new architecture is more maintainable, more testable, and better separated. The centralized gateway service makes it easier to add new external integrations and handle failures consistently.

But this only pays off because we’re building a system with multiple external integrations, team coordination requirements, and long-term maintenance needs. The complexity tax becomes worthwhile when the problems justify the tools.

NestJS makes sense when you have:

- Large teams (15+ developers) needing enforced consistency across multiple services

- Complex domains requiring extensive validation, authorization, and business rule coordination

- Long-term maintenance where modular architecture benefits outweigh development velocity costs

- Enterprise requirements for observability, compliance, and operational consistency

Simpler approaches make sense when you have:

- Small teams (2-10 developers) prioritizing rapid iteration and fast feedback loops

- Straightforward domains where business logic complexity doesn’t require framework abstractions

- Performance requirements where framework overhead impacts user experience

- Experienced developers who can maintain consistency without framework enforcement

The Architectural Choice Framework

The key insight from this experience is that architectural decisions should optimize for current requirements while remaining flexible enough to evolve, not for hypothetical future problems that may never materialize.

Instead of asking “What’s the most sophisticated solution?” or “What would Netflix use?”, ask:

- What problems do we actually have today? – Don’t solve coordination problems you don’t have

- Can we solve this more simply? – Prefer solutions that match problem complexity

- What are the real failure modes? – Optimize for problems that actually hurt your users

- How will this affect debugging? – Choose tools that make problems easier to find and fix

- What’s the team knowledge cost? – Factor learning curves into architectural decisions

The trap we fell into was choosing based on aspirational complexity rather than current reality. We imagined we’d eventually need enterprise patterns, so we adopted them early. But architectural decisions should serve today’s problems while enabling tomorrow’s growth, not create today’s problems for tomorrow’s hypothetical benefits.

The Real Lesson About Type Safety

The 72-hour debugging nightmare wasn’t caused by bad code or poor practices, it was caused by choosing tools that systematically bypass the safety mechanisms we depend on. TypeScript’s promise of “JavaScript with safety” breaks down when frameworks require you to abandon type checking in critical areas.

Dependency injection’s promise of “flexible, testable code” breaks down when the flexibility enables errors that strict typing would prevent. The ceremony of enterprise patterns doesn’t compensate for the loss of compile-time verification.

For backend development, where correctness is paramount and debugging failures are expensive, tools that make errors impossible to compile often serve you better than tools that make correct usage easier to express.

The choice between safety and sophistication should be deliberate and aligned with actual requirements. Runtime flexibility isn’t worth much if your runtime doesn’t work reliably.

Choose Your Guarantees Carefully

The lesson isn’t that sophisticated frameworks are universally bad, it’s that the choice between flexibility and correctness has real consequences for development velocity, debugging complexity, and system reliability.

After this experience, I’m convinced that for most backend services, the guarantees provided by strict typing and explicit dependencies matter more than the expressiveness provided by sophisticated frameworks. The cognitive overhead of understanding framework mechanics often exceeds the benefit of framework features.

This doesn’t make NestJS a bad framework. For teams actually dealing with large-scale coordination problems, complex business domains, and established development processes, its structured approach provides real value. The framework works well when your problems match its strengths.

But for teams building straightforward services, the framework’s complexity tax, in debugging time, test maintenance, and knowledge requirements, often exceeds its benefits. Starting simple and adding complexity as problems actually emerge is usually more sustainable than adopting complex patterns preventively.

The next time we evaluate frameworks, I’ll ask different questions: “What problems do we actually have today?” rather than “What problems might we have someday?” and “Can we solve this more simply?” rather than “What’s the most sophisticated solution?”

Choose your complexity deliberately. Choose your type safety carefully. Your future debugging self will thank you for the honesty.

This post is based on real refactoring experiences with enterprise Node.js applications. While specific APIs and business logic are anonymized, the complexity patterns, time investments, and debugging challenges reflect authentic developer experience I faced during the implementation.

Leave a Reply